|

to place orders please stop by at our our online shop @

History / Background: The Duduk (pronounced “doo-dook”) is one of the oldest double reed instruments in the world. Indeed, it’s origins can be traced back to at least before the time of Christ. Of all the traditional instruments played in Armenia today, only the duduk is said to have truly Armenian origins. This seems to be supported by the fact that, unlike the duduk, all of these other instruments can trace their lineage’s back to the Arabic world and to the countries of the Silk Road. Throughout the centuries, the duduk has traveled to many neighboring countries and has undergone a few subtle changes in each of them, such as the specific tuning and the number of holes, etc. Now variants of duduk can be found in Georgia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Persia, and even as far away as the Balkans. Besides being called variations of the Armenian word “duduk”, such as “duduki” (in Georgia), it is also referred to as “mey” (in Turkey), and “balaban” (in Azerbaijan and in parts of Central Asia). The basic form has changed little in it’s long history. Originally, like many early flutes, the instrument was made from bone. Then it advanced to a single, long piece of reed/cane with the mouthpiece fashioned on one end and holes drilled out along it’s length for the notes. However, this had the obvious disadvantages of a lack of durability, namely when any part of it would crack you had to make an entirely new instrument, and perhaps equally frustrating, it could not be tuned. So, to address both of these problems, it was eventually modified into two pieces: a large double reed made of reed/cane; and a body made of wood. This is the form that is still in use today. While other countries may use the wood from other fruit and/or nut trees when making their instruments (often plum and walnut in Georgia, and Azerbaijan, for example...), in Armenia, the best wood for making duduks has been found to be from the apricot tree. It has come to be preferred over the years for it’s unique ability to resonate a sound that is unique to the Armenian duduk. All of the other variations of the instrument found in other countries have a very reed-like, strongly nasal sound, whereas the Armenian duduk has been specifically developed to produce a warm, soft tone which is closer to a voice than to a reed. It should be noted that in order to further accentuate these qualities, a particular technique of reed making has evolved, as well. While recent appearance’s of the duduk in various movie and TV soundtracks (“The Last Temptation of Christ”, “The Crow”, “Zena, Warrior Princess”, etc...) has accentuated it’s evocative and soulful side (and understandably so!...), it may surprise some to find that it is also quite capable of a wide range of melodies, including rhythmic dance tunes. It may very well be because of this wide range of expression, combined with the depth and power of it’s sound, that the duduk has truly become a part of everyday life in Armenia. In fact, it would not be an exaggeration to say that no wedding, festive occasion, or family gathering would be complete without a duduk player...

The Instrument itself:

The reed, called ”Ramish” in Armenian (pronounced “rah-meesh”), is basically a tube made of reed/cane that has been flattened on one end (and left cylindrical at the other), whose shape closely resembles a duck’s bill. It can be anywhere from 3” to 4.5” long, and 3/4” to 1 1/4” wide depending on the maker and the key of duduk it corresponds to. The fact that the opposite sides of the tube come together, and thus produces the sound, makes this a double reed. Because the reed expands as it is played, a small bridle is used to regulate the aperture of the reed. Connected to this bridle is a small cap that is used to keep the reed closed when it is not being played. It is important that the reed be only open enough to play comfortably (and be in tune with itself), because if it gets too wide, it will be very difficult to blow and it will cause the instrument to be flat.

Now, this being said, it may be necessary to actually wet the reed in

order to open it up. If the reed is dry (because it’s new or hasn’t been

played in a while), then you will need to run a little water into the

inside and while closing the circular end with your thumb, shake the

water to coat the inside of the reed and either blow it out the closed

side or tip it over and dump the water out. Next, making sure you have

the closing cap on, stand the reed upright and wait a few minutes until

it opens slightly on it’s own. The trick here is to lightly coat the

inside with moisture, so that the reed can just be coaxed to open. If

the reed is too wet, it will open too much and the pitch will move

around a lot when you play. Playing the duduk is already hard enough, do

not do something that will make it even harder!

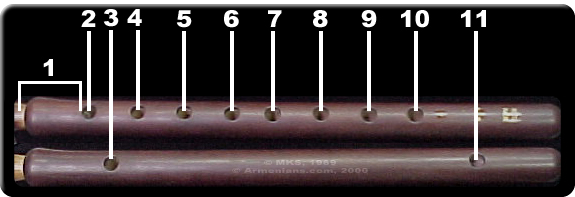

The Armenian duduk itself is a cylindrical tube made of apricot wood, and as you can see in the above photo, it has eight playable finger holes on one side of the instrument, with a single thumb hole on the back for the top hand (labeled #3 in the photo). There is a tenth hole (labeled as #11 in the photo) that is needed for tuning, and depending on the maker it can be located on the top or on the bottom of the instrument (Master Karlen, “MKS”, and Master Souren, “SAM”, put their holes on the bottom, while Master Ruben, “RR”, puts his on the top). While you hardly use this tenth hole, the benefit to having the hole on the bottom is that you will be able to play that note either by pulling the instrument to your stomach (with all of the holes closed) if you are standing, or by using your knee if you are sitting. The Armenian duduk is a deceptively simple instrument. It’s range is primarily a single octave, with a couple of notes above and below at either end. It is untempered and diatonic, and it is available in a range of keys (depending on the maker). What makes the instrument so difficult is that all of the chromatic intervals are made by half-holing each note, you do not use any “forked-tuning” when playing the duduk. To make this easier, however, the holes have been made relatively large compared to the overall size of the instrument. This allows for more “play” between the notes, and it contributes to the rich, full sound of the instrument. Keep in mind that this also means that you have to blow harder to get that sound, as well as work harder in order to keep the notes in tune...something that is very difficult in the beginning, but well worth it in the end!

Set Up and Playing the Instrument: Setting up and playing the duduk pretty much comes down to preparing the reed itself, and then fitting it into the socket of the duduk.

What to look For: To begin, the ramish needs to be un-cracked and in good shape in order to be truly playable. The only exception to this is if the crack is along the folded edge, then it should still be fine (depending on how deep it is). Most high quality reeds come with a thin strip of leather glued to both of the folded edges of the reed (see the “ramish” photos above) which serves to seal up any potential air-loss, as well as to control the expansion of any present or future cracks. If your reed has a crack, and you don’t already have these leather strips on, you can add them yourself. Find a source of leather pieces (a shoe or clothing repair shop will often just have a bag of scraps you can take for free) and using the treated side of the skin, peel off just the treated layer. You want it to be as thin as possible, otherwise the bridle will not fit and the reed will not resonate well. Cut off a strip and shape it to fit your reed. Then, using a thin layer of carpenters/wood glue apply the strip along the edge of the reed. Let it dry completely, then try it out. Remember to remove the bridle when working on the reed, and if the reed is open at all, you should be sure to keep the closing cap on at all times.

As discussed above in the reed description, if the reed is closed, then the goal of the player is to get the reed just moist enough so that it opens slightly (see above photo). It is important to not over soak the reed because if you do it will open too much, making it very difficult to play and it will throw the tuning off for the whole instrument. Once again, just shake a little water in the inside of the reed, blow it out, put the closing cap on it, then stand it up. After a few minutes, the ramish should open. If not, repeat the process until it does. However, if the reed has been played recently or just happens to be one that opens easily, you may not need to add water to it. It may be sufficient to just place it in your open mouth and breath hot air onto it until it opens.

Connecting the Reed to the Duduk:

Once the reed has opened it can now be attached to the duduk’s body. It

is important to attach the reed so that it is snug, but you must be

careful not to crack it when inserting it. It helps if you hold the

ramish like you would hold a banana (ie. with the fingers loosely

wrapped around it) with the playing end up towards your thumb, and the

connecting end down (see photo “A” above). Then, with the duduk in one

hand and the reed in the other, place the ramish into the socket at the

upper end of the duduk and connect the two with a slight twisting motion

(this serves to help lock the reed in). Align the reed so that the flat

plane of the reed is perpendicular to the holes (see photo “B” above),

You can “sight” this with your eyes, just like you would look down the

barrel of a gun. Also, each reed has it’s own particular curvature, and

generally, you want the angle that it comes out of the duduk to slope

down as it comes to your lips (see photo “C” above) If you are lucky enough to get a hold of a good instrument that has been matched to it’s reed, (ie. in tune, and already fitted!), then you are doing great. However, if this is not the case, or you acquire more reeds as time goes by, it will be more likely that you will need to adjust them to fit your duduk. You can test to see if the ramish needs to be adjusted by first checking each individual note (with a tuner or piano), then you should check an octave interval to make sure the reed-itself is open to the right aperture. This is done by comparing the note you get with all the fingers off, to the note you get with six fingers and your thumb closed on the instrument (this translates to #1 and #8 on the above fingering diagram). If you have a good instrument and your reed is properly adjusted, these two notes should be in tune. (Keep in mind that when you play any of the top three holes of your duduk, you must release some of the tension on the reed with your lips, as well as close the bottom four holes with your lower hand at the same time or else the notes will be sharp). If, after you check everything, you feel that an adjustment is needed, you will need to fine tune the instrument. This is done by wrapping or unwrapping the thread on the reed. Basically, as you add thread, the reed no longer goes in as far and therefore the distance between the reed and the holes is slightly larger. This then has the effect of flatting the tuning. The opposite is equally true, if you remove thread from the reed, you will shorten the distance between the ramish and the holes, and it will make the tuning sharper. In fact, the duduk needs to be tuned by following a two step process. First, you need to begin by determining your comfort level regarding how much the reed itself is open when you play (remember when determining this aperture that being able to regulate that note with the bridle and your lips must be taken into account, as well). Then, once this is set, the ramish itself is adjusted to the duduk by wrapping or unwrapping the thread in order to find the correct distance between it and the holes. You will need to find the balance between these two components. Up to now, all of this information is based on the assumption that you have the correct sized ramish for the duduk you want it to go to. There are many different keys of duduks, and therefore, are there many differently-sized ramish to fit them. It must be taken into account that this fine tuning is for when the reed is close to the pitch that the duduk should be in. You may be able to adjust the tuning by as much as a half step, but that is really pushing it. In general, you will only be able to comfortably get about a quarter tone of correction with each reed. This being said, however, some reeds will not fit deep enough into the socket of the duduk because the reed itself is too big. In this case, you will need to unwrap the thread off of the ramish and sand the base down until it goes in as far as you would like. Be very careful, as it is easy to go too far. Remember, you can always take more off, but there is limit as to how much thread you can wrap to make up for lost material. Just for the sake of information: If you are sure that the reed is the right size for your duduk, and you have unwrapped as much thread as you safely can before the reed falls out of the socket, and it is still flat of the note that it should be at (make sure you have the right note), then it is possible to sand the playing side of the duduk in order to shorten it up, and therefore sharpen the overall tuning. This is a very delicate procedure and you risk truly ruining your reed. Do not attempt this unless you are completely sure of what you are doing. In general, if you are buying decent reeds, then the reed makers have done this part for you and you should only need to do the fine tuning portion in order to adjust it to your particular duduk. It is interesting to note that most duduk players eventually wind up with several duduks in the same key because the same reed in different duduks will be subtly different. In fact, some duduks are slightly sharper on the top and so they match well with a flatter reed, and some duduks have the ability to slightly flatten and round out the sound of a reed that might otherwise be too sharp in another instrument. On the other hand, this same duduk might seem slightly flat with another reed!

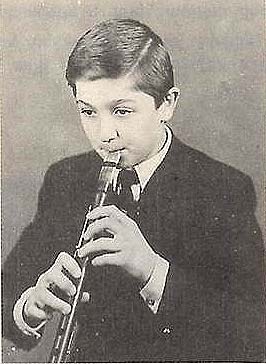

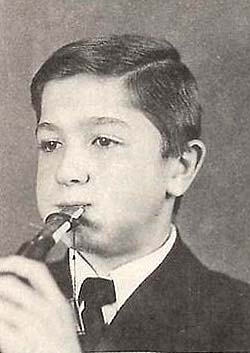

Playing the duduk: The Armenian duduk is a very simple and organic instrument, and it allows for a great deal of individual expression. To begin, it requires a great deal of breath, so proper posture and being relaxed is important. The breath control is exactly like that of a singer, or an actor, in that you should breath from your diaphragm, and not your chest. Do not slouch, or bow your head, this will only block your breath/energy and make you work even harder to play the instrument! (see photo above)

The reed, while being quite large, only gets played at the very end, with only 1/4” to 1/2” being inserted into your mouth (see above photo). It should not touch your teeth, and your upper and lower lips should be secure on it just enough to make it vibrate without any loss of air. It is important to note that, unlike a clarinet, it does not need to be squeezed against the lips, because you can actually pinch off your sound. The cheeks are allowed to puff out a little, this actually helps your embouchure. The correct way to do a vibrato is by moving your lower lip only, and not by moving your jaw.

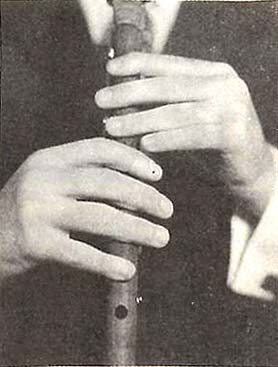

The fingers are relaxed, at ease, and slightly curved. It may help to think of this looseness as beginning in your arms, then flowing down into your wrists, and hands. The fingers are spaced in two separate ways, depending on the needs of the tune you are playing (see photo). In general, if you only need the top seven fingers (not counting the thumb hole), then the top hand uses three fingers and the bottom uses all four. However, if you will need all eight notes in the piece you will be playing, then both hands use all four fingers each (this includes using the thumb on the top hand, of course). Notice that between these two positions, there is a slight shift of where the fingers fall on the holes for the top hand only. As mentioned in the tuning section, when you play the top four notes (#1 through #5 on the fingering chart), you will want to keep all of the notes on the lower hand closed. This not only will keep the top notes from being too sharp, it also allows more of your instrument to resonate and therefore the sound will be better. When you begin to play the duduk, you will soon learn that playing is tuning....You must always be adjusting the reed in order to keep your pitch correct, and you do this by getting it as close as you can with the bridle before you start, and then you have to use your lips and fingers while your playing. (Most likely this will mean that you will pinch the reed slightly for the lower notes, and release the reed for the higher ones).

You should begin by playing the holes all the way off and on. Then when this becomes easier, start to work on your half-hole technique (see above photo). You will need to get a feel for where the actual note is (it’s good to use a piano) and then work on hitting it right from the start without it sliding around. You will also notice that you need to blow harder to maintain the volume as compared to the completely open notes. Then put it in sequence with other notes. You should ultimately be able to half-hole cleanly on every note, and not be able to tell which notes are full and which ones are half-holed. It is interesting to note that in Armenia, duduks are traditionally played in pairs, with one person playing the melody and one person playing a continuous drone note called the “dam”, or “damkash”. In Armenia, it is common for the student to hold the note for the teacher as part of his learning the instrument because it helps to develop the muscles, as well as to perfect their intonation. This “circular breathing” is done by puffing up the cheeks with air while you are playing, then when you need to breath, you cut off the air in your throat At his point, you simultaneously use the reserved air in your cheeks to keep the note going as you refill your lungs through your nose. You then reengage your lungs and the note never falters...It may help to use an analogy here: think of the whole process as if you were releasing and then reengaging the clutch in the manual transmission of a car, while keeping it in the same gear. Your cheeks are the clutch.

Some Final Words: While it may be true that the Armenian duduk has recently evolved along Western lines (namely that it is now diatonic and tuned in a major (natural) scale- thereby making it capable of holding it’s own with tempered instruments), it is not really a completely Western instrument. In fact, it’s expressiveness and style of play have it firmly rooted in the East. Perhaps it is because of this very dichotomy that it has the universal appeal that it does?...Who knows? One thing is for sure, though, and that is that even though the technique for playing the duduk may take years to perfect, when you finally get there, you will have attained a level of direct control and expressiveness that no other instrument can give you...which is probably what drew you to the duduk in the first place!... Congratulations, and good luck.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||